Having recently written about character references in HTML and escape sequences in CSS, I figured it would be interesting to look into JavaScript character escapes as well.

Character codes, code points, and code units

A code point (also known as “character code”) is a numerical representation of a specific Unicode character.

For example, the character code of the copyright symbol © is 169, which can be written as 0xA9 in hex.

In JavaScript, String#charCodeAt() can be used to get the numeric Unicode code point of any character up to U+FFFF (i.e. the character with code point 0xFFFF, which is 65535 in decimal).

Since JavaScript uses UCS-2 encoding internally, higher code points are represented by a pair of (lower valued) “surrogate” pseudo-characters which are used to comprise the real character. To get the actual character code of these higher code point characters in JavaScript, you’ll have to do some extra work. Basically, JavaScript uses code units rather than code points.

Now that’s out of the way, let’s take a look at the different types of character escape sequences in JavaScript strings.

Single character escape sequences

There are some reserved single character escape sequences for use in strings:

\b: backspace (U+0008 BACKSPACE)\f: form feed (U+000C FORM FEED)\n: line feed (U+000A LINE FEED)\r: carriage return (U+000D CARRIAGE RETURN)\t: horizontal tab (U+0009 CHARACTER TABULATION)\v: vertical tab (U+000B LINE TABULATION)\0: null character (U+0000 NULL) (only if the next character is not a decimal digit; else it’s an octal escape sequence)\': single quote (U+0027 APOSTROPHE)\": double quote (U+0022 QUOTATION MARK)\\: backslash (U+005C REVERSE SOLIDUS)

All single character escapes can easily be memorized using the following regular expression: \\[bfnrtv0'"\\].

Note that the escape character \ makes special characters literal.

There’s only one exception to this rule:

'abc\

def' == 'abcdef'; // trueThe \ followed by a new line is not a character escape sequence, but a LineContinuation. The new line doesn’t become part of the string. This is simply a way to spread a string over multiple lines (for easier code editing, for example), without the string actually including any new line characters. I suppose you could think of \ followed by a new line as an escape sequence for the empty string.

Characters without special meaning can be escaped as well (e.g. '\a' == 'a'), but this is of course not needed. However, using \u outside of a Unicode escape sequence, or \x outside of a hexadecimal escape is disallowed by the specification, and causes some engines to throw a syntax error.

Note: IE < 9 treats '\v' as 'v' instead of a vertical tab ('\x0B'). If cross-browser compatibility is a concern, use \x0B instead of \v.

Another thing to note is that the \v and \0 escapes are not allowed in JSON strings.

Octal escape sequences

Any character with a character code lower than 256 (i.e. any character in the extended ASCII range) can be escaped using its octal-encoded character code, prefixed with \. (Note that this is the same range of characters that can be escaped through hexadecimal escapes.)

To use the same example, the copyright symbol ('©') has character code 169, which gives 251 in octal notation, so you could write it as '\251'.

Octal escapes can consist of two, three of four characters. '\1', '\01' and '\001' are equivalent; zero padding is not required. However, if the octal escape (e.g. '\1') is part of a larger string, and it’s immediately followed by a character in the range [0-7] (e.g. 1), the next character will be considered part of the escape sequence until at most three digits are matched. In other words, '\12' (a single octal character escape equivalent to '\012') is not the same as '\0012' (an octal escape '\001' followed by an unescaped character '2'). By simply zero padding octal escapes, you can avoid this problem.

Note that there’s one exception here: by itself, \0 is not an octal escape sequence. It looks like one, and it’s even equal to \00 and \000, both of which are octal escape sequences — but unless it’s followed by a decimal digit, it acts like a single character escape sequence. Or, in spec lingo: EscapeSequence :: 0 [lookahead ∉ DecimalDigit]. It’s probably easiest to define octal escape syntax using the following regular expression: \\(?:[1-7][0-7]{0,2}|[0-7]{2,3}).

Note that octal escapes have been deprecated in ES5:

Past editions of ECMAScript have included additional syntax and semantics for specifying octal literals and octal escape sequences. These have been removed from this edition of ECMAScript. This non-normative annex presents uniform syntax and semantics for octal literals and octal escape sequences for compatibility with some older ECMAScript programs.

Additionally, they produce syntax errors in strict mode:

A conforming implementation, when processing strict mode code (see 10.1.1), may not extend the syntax of

EscapeSequenceto includeOctalEscapeSequenceas described in B.1.2.

They’re disallowed in template literals as well.

TL;DR Don’t use octal escapes; use hexadecimal escapes instead.

Hexadecimal escape sequences

Any character with a character code lower than 256 (i.e. any character in the extended ASCII range) can be escaped using its hex-encoded character code, prefixed with \x. (Note that this is the same range of characters that can be escaped through octal escapes.)

Hexadecimal escapes are four characters long. They require exactly two characters following \x. If the hexadecimal character code is only one character long (this is the case for all character codes smaller than 16, or 10 in hex), you’ll need to pad it with a leading 0.

For example, the copyright symbol ('©') has character code 169, which gives A9 in hex, so you could write it as '\xA9'.

The hexadecimal part of this escape is case-insensitive; in other words, '\xa9' and '\xA9' are equivalent.

You could define hexadecimal escape syntax using the following regular expression: \\x[a-fA-F0-9]{2}.

It’s a bit confusing that the spec refers to this kind of escape sequence as “hexadecimal”, since Unicode escapes use hex as well.

Unicode escape sequences

Any character with a character code lower than 65536 can be escaped using the hexadecimal value of its character code, prefixed with \u. (As mentioned before, higher character codes are represented by a pair of surrogate characters.)

Unicode escapes are six characters long. They require exactly four characters following \u. If the hexadecimal character code is only one, two or three characters long, you’ll need to pad it with leading zeroes.

The copyright symbol ('©') has character code 169, which gives A9 in hexadecimal notation, so you could write it as '\u00A9'. Similarly, '♥' could be written as '\u2665'.

The hexadecimal part of this kind of character escape is case-insensitive; in other words, '\u00a9' and '\u00A9' are equivalent.

You could define Unicode escape syntax using the following regular expression: \\u[a-fA-F0-9]{4}.

Note: Other than a few simple escapes, Unicode escapes are the only ones allowed by the JSON specification.

ECMAScript 6: Unicode code point escapes

ECMAScript 6 introduces a new kind of escape sequence in strings, namely Unicode code point escapes. Additionally, it will define String.fromCodePoint and String#codePointAt, both of which accept code points rather than UCS-2/UTF-16-like code units.

When this is implemented, any character can be escaped using the hexadecimal value of its character code, prefixed with \u{ and suffixed with }. This is allowed for code points up to 0x10FFFF, which is the highest code point defined by Unicode.

Unicode code point escapes consist of at least five characters. At least one hexadecimal character can be wrapped in \u{…}. There is no upper limit on the number of hex digits in use (for example '\u{000000000061}' == 'a') but for practical purposes you won’t need more than 6, unless you perform unnecessary zero-padding.

The tetragram for centre symbol (𝌆) has code point U+1D306, so you could write it as \u{1D306}. For comparison, if you were to use simple Unicode escapes to represent this symbol, you’d have to write out the surrogate halves separately: '\uD834\uDF06'.

The hexadecimal part of this kind of character escape is case-insensitive; in other words, '\u{1d306}' and '\u{1D306}' are equivalent.

You could define Unicode code point escape syntax using the following regular expression: \\u\{([0-9a-fA-F]{1,})\}.

Control escape sequences

In regular expressions (not in strings!), any character with a character code greater than 0 and lower than 26 can be escaped using its caret notation character, prefixed with \c.

Control escapes are three characters long. They require exactly one character following \c.

For example, U+000A LINE FEED is ^J in caret notation (because 0x000A === 10 and J is the 10th letter of the alphabet). So, a valid regular expression that matches this symbol would be /\cJ/, e.g. /\cJ/.test('\n') == true.

The caret notation character following \c in this kind of character escape is case-insensitive; in other words, /\cJ/ and /\cj/ are equivalent.

Here’s a list of all the available control escape sequences and the control characters they map to:

| Escape sequence | Unicode code point |

|---|---|

\cA or \ca |

U+0001 START OF HEADING |

\cB or \cb |

U+0002 START OF TEXT |

\cC or \cc |

U+0003 END OF TEXT |

\cD or \cd |

U+0004 END OF TRANSMISSION |

\cE or \ce |

U+0005 ENQUIRY |

\cF or \cf |

U+0006 ACKNOWLEDGE |

\cG or \cg |

U+0007 BELL |

\cH or \ch |

U+0008 BACKSPACE |

\cI or \ci |

U+0009 CHARACTER TABULATION |

\cJ or \cj |

U+000A LINE FEED (LF) |

\cK or \ck |

U+000B LINE TABULATION |

\cL or \cl |

U+000C FORM FEED (FF) |

\cM or \cm |

U+000D CARRIAGE RETURN (CR) |

\cN or \cn |

U+000E SHIFT OUT |

\cO or \co |

U+000F SHIFT IN |

\cP or \cp |

U+0010 DATA LINK ESCAPE |

\cQ or \cq |

U+0011 DEVICE CONTROL ONE |

\cR or \cr |

U+0012 DEVICE CONTROL TWO |

\cS or \cs |

U+0013 DEVICE CONTROL THREE |

\cT or \ct |

U+0014 DEVICE CONTROL FOUR |

\cU or \cu |

U+0015 NEGATIVE ACKNOWLEDGE |

\cV or \cv |

U+0016 SYNCHRONOUS IDLE |

\cW or \cw |

U+0017 END OF TRANSMISSION BLOCK |

\cX or \cx |

U+0018 CANCEL |

\cY or \cy |

U+0019 END OF MEDIUM |

\cZ or \cz |

U+001A SUBSTITUTE |

You could define control escape syntax using the following regular expression: \\c[a-zA-Z].

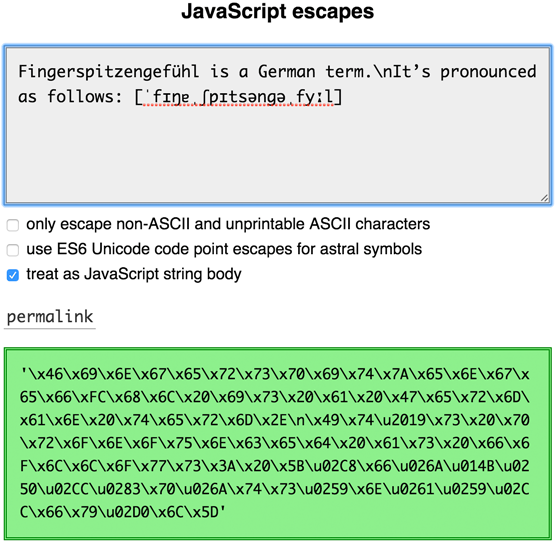

A tool for character escapes

I wrote a JavaScript string escaper that combines these different kinds of escapes (except the deprecated octal escapes) and returns the smallest possible result string. Try it at mothereff.in/js-escapes!

You can use it to escape any character, but there’s an option to only escape non-ASCII and unprintable ASCII characters (which is probably the most useful). This way, you can easily turn strings such as 'Ich ♥ Bücher' into its smallest possible ASCII-only equivalent 'Ich \u2665 B\xFCcher'. Back when I was working on Punycode.js unit tests, this tool saved me quite some time.

Need to escape strings in your JavaScript app? The JavaScript library that powers this tool is available on GitHub.

Comments

pomeh wrote on :

Thanks Mathias! This is awesome :)

Deian wrote on :

You are one of the most REALLY useful developers around. Thank you for all of your articles Mathias! Wish you a Merry Christmas & Happy New Year

.mario wrote on :

Visual Basic Script allows to use yet another form of escape to represent decimal numbers:

&Hxxor&hxxrepresents numeric values (Hexa-decimal)&Oxxxor&oxxxrepresents numeric values (Octal)&xxxor&xxxrepresents numeric values (Octal, no O is required)Thiemo wrote on :

I did something very similar as a 140byt.es entry once: http://maettig.com/code/javascript/encode-javascript-string-in-140byt.es.html

Nils wrote on :

What if I need to insert

\itself into the string, i.e. not using it as escape character? I’m lost… Tried\, but the compiler just leaves it that way…Update: Sorry, I forgot to mention the language: JS, using JSON, trying to add data to a Google Sheet cell through a modified ‘Blockspring’ function.

Mathias wrote on :

Nils: Use

\\.Flimm wrote on :

If you're not careful to add the padding in regexes, it can act strangely:

Mathias wrote on :

Flimm: The padding is required, not just in regular expressions, but everywhere.

\u0and\u7fare not valid escape sequences.Stan wrote on :

Thanks! I was trying to get

œencoded using\x153and couldn’t figure out why it wasn’t working until I saw that hex codes only work to\xFFand that I needed to use\u0153.